Guard Your Mental

May Is Mental Health Awareness Month — My, How Hip-Hop Has Grown

As a Black youth who came of age in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in the 1990s, I do not recall much communal dialogue about the value of good mental health. I grew up in a culture that shunned those who struggled with their mental faculties and designated them as crazy. My community believed that having devout faith in God was the catch-all cure for any “afflictions” one might be facing and so were generally averse to the idea of therapy.

Therapy, as it was framed in my community, was a luxury that white people could afford to engage with. My parents, who were first-generation college students, came from large rural Louisiana families who did not have time or access to mental health providers. And even if mental health support was available, they didn’t feel able to access it; they were products of a generation that assigned shame to Black people who seemingly were unable to “keep it together.”

In their eyes, relying on guidance from professionals was, by their assessment, to display compromised faith in “The Almighty " or, worse, to wear the “crazy” label they often callously assigned to those whose behavior was deemed to be outside the realm of normalcy.

By the time I was a teenager in the early ’90s, hip-hop was rising to the forefront of modern music and was, in many respects, synonymous with Black culture. As a Black teenage boy, I was enamored with hip-hop culture's creativity, style and language, largely because of how its most prominent figures embodied swagger, hyper-masculinity and effortless cool. The rappers I grew up on presented an unbothered and authoritative sense of self that was appealing. Their larger-than-life personas provided a representation of (primarily) Black manhood that navigated the world with a level of autonomy that seemed otherworldly in comparison to the social climate I was raised in.

2 Pac, The Notorious B.I.G., and Redman at Club Amazon; July 23, 1993; Getty Images

As the genre grew, and its inclusion expanded from its East Coast origins and West Coast ubiquity to it taking center-stage in the “Dirty South,” the hip-hop titans of my youth were nothing short of superheroes. Unflappable, fully confident urban griots who spoke freely, created pathways and got paid handsomely to express themselves. The teenage version of me never once considered that their lyrics, which often centered on hyper-sexuality, drug and alcohol abuse and violence, were a potential cry for help or in response to deep-rooted trauma.

I believed hip-hop had everything under control, even as some of its brightest stars showed signs of spiraling out of orbit.

By the time hip-hop became the top-selling genre in music in the late 2010s, the chinks in its seemingly invincible armor were becoming increasingly visible to the public. The time between my teenage years and young adulthood ushered in an era of highly regarded emcees whose output was significantly more vulnerable than many of their predecessors.

Artists such as Kid Cudi, Wale, J. Cole, Kanye West and others ascended to the top of the charts with narratives that were not characterized by “tough guy” imagery. Granted, many of these acts still trafficked in damaging hip-hop tropes (i.e., rampant misogyny and excessive materialism), but still, there was newfound appreciation for their approach. “The culture” was witnessing an emergence of popular artists who appeared unafraid to rhyme about topics such as anxiety, depression and suicide ideation, and their openness on wax, as well as in interviews, was starting to slip past the long-standing borders hip-hop had placed in front of itself and its creators.

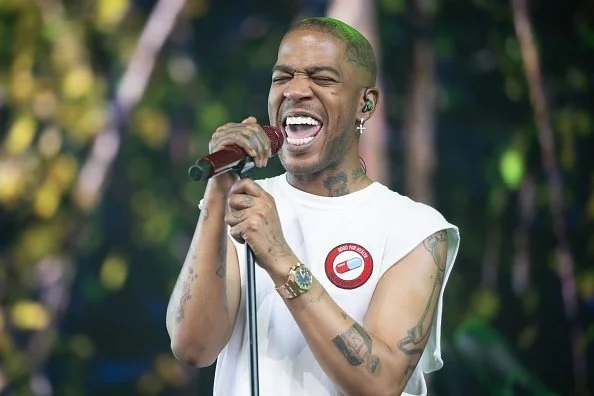

Kid Cudi at the 2024 Coachella Music Festival; Getty Images

Hip-hop’s 21st-century evolution of artists who pushed the envelope around topics of mental health or expressed vulnerability in their music was not totally without precedent. Emcees such as De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest and even notable “gangsta rappers” such as the Geto Boys were penning rhymes back in the ’90s that broke the mold of hip-hop’s rugged exterior, but as the larger conversation around mental health expanded in Black and Brown communities, more of the music reflected heightened sensitivities around topics formerly thought of as taboo.

Yet this genre that prided itself on being uncensored, raw and authentic was just starting to grow into a more genuine version of itself at the turn of the millennium. Hip-hop began embracing the nuanced personhood of its creators and allowing itself to shed the bulletproof persona that might have excited its earliest audiences, but was stifling its maturation.

As a now middle-aged hip-hop head, I am appreciative of its progression regarding its stance on mental health awareness. As a writer/artist diagnosed with general anxiety disorder, I am inspired by the culture’s growth as it relates to its advocacy around wellness, as well as its artists who are courageous enough to inform the world of their struggles.

The month of May is designated as Mental Health Awareness Month, a time dedicated to raising awareness about mental health, reducing stigma and promoting mental well-being. Incidentally, this recognition comes just ahead of Black Music Month in June, a period designed to appreciate the contributions of African-American musicians, composers, singers and songwriters in American culture.

With hip-hop being one of the most consequential genres in the history of Black American music, it feels like universal alignment that in May there is a focus on minimizing stigma around mental health and promoting well-being, and in June a month-long dedication to Black music will recognize some of the world’s most impactful creators.

Many of them are the lyricists, emcees and poets who amplified the power of the art form and freed the culture by sharing uncomfortable truths.